Your House on Campus

The Long Answer to the Question Everyone Has ...

Learn more about the high cost of building a better university from this in-depth article by Donald Guckert and Jeri Ripley King, APPA Fellows.

“You’ve got to be kidding! I could build a nice house for that amount!!”

How many times have we heard that the cost of a “simple” renovation would buy a high-end home in a nice neighborhood? Customers typically react with sticker shock over the cost of a campus renovation when they receive the initial project estimate. This is the point at which worlds collide, where the institutional construction world of the project manager meets the customer’s residential construction frame-of-reference.

Trying to justify the costs of institutional construction within a residential frame of reference is not easy. These two types of construction are a world apart. However, just for the fun of it, we wondered what would it take to renovate your house into a campus facility? Let’s suppose this facility is located on campus and you request that we renovate the living room into a classroom, the kitchen into a lab, and the bedroom into an office. Let’s take a walk through your house to see what we will need to do.

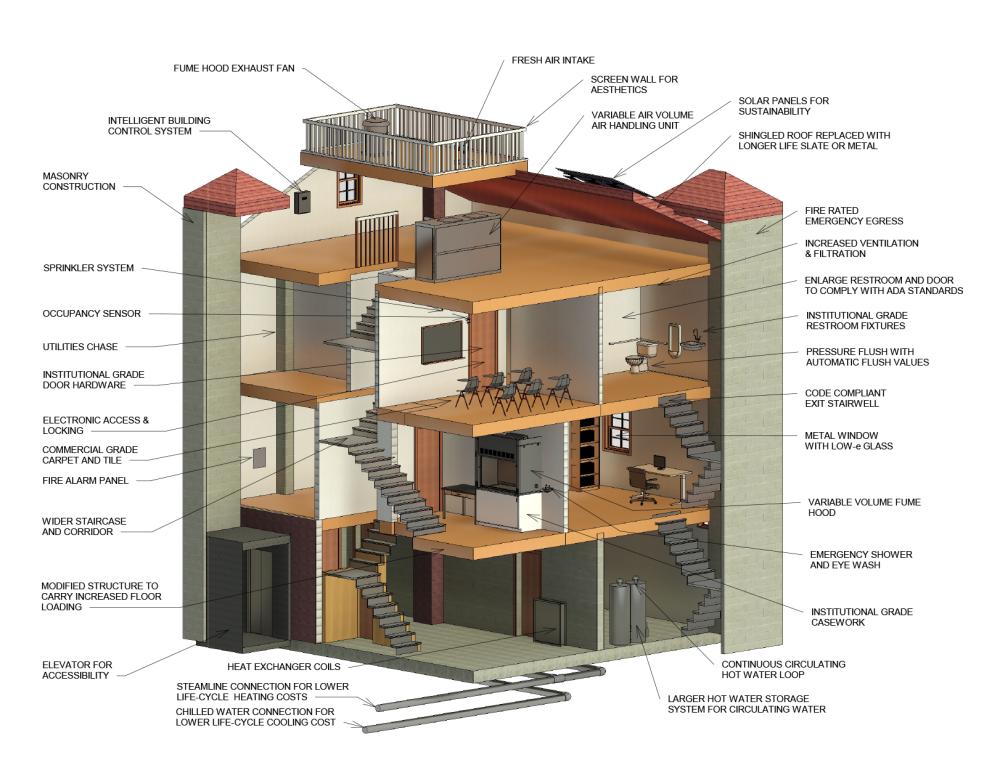

To begin with, we’ll need to make the facility safe and accessible. We’ll add an elevator to the second floor, and an exit stair tower connecting all floors to the outside. To make this building look like it belongs on our campus, we’ll arrange for matching towers and give the building an identifiable look. Unfortunately, this will add considerable cost and space to the building, while not adding any space for program needs. After we widen the interior hallways and stairways for increased traffic and install a utility chase from the basement to the attic, we will actually reduce the amount of assignable space.

As a university facility, the house will fall under a different classification as far building codes are concerned. This means we’ll need to replace the $20 battery-operated smoke detectors with a $20,000 fire protection system. This system, which includes a fire alarm panel, wired sensors, and sprinkler system, meets all of the requirements of the local fire marshal. To inhibit the spread of flames and smoke from one room to another, we have to reconstruct the walls that separate the rooms from the hallway and make them fire-rated walls. This is not cheap! Neither are the solid doors mounted to the metal doorframes that we’ll use to replace the house’s hollow doors and wooden frames. For durability we’ll need to upgrade all the door hardware. Installing a new card access system will bring us into compliance with institutional policies pertaining to safety and security.

We know the budget for this renovation is limited. Before the money runs out, we need to look at the mechanical systems. By code, our lab, classroom, office and restroom spaces require controlled outside ventilation that your house doesn’t have. The small air conditioning unit and gas furnace will have to go. With the big increase in filtered airflow, it wouldn’t keep up after the first five minutes. Our house will need dependable and code-compliant mechanical systems. For redundancy and efficiency, we’ll connect to chilled water and steam from our central utilities plant.

Finally, we move to the kitchen. To convert it to a lab, we’ll take out the $800 kitchen stove and hood, and replace it with a $35,000 variable flow fume hood. Fortunately, we won’t need a strobic air fan for that hood; you don’t even want to think about that cost. Those kitchen cabinets will come out to allow for the built-in lab casework. The refrigerator will have to go, too. In its place will be a $15,000 environmental chamber.

We’ll open up the walls when we install the lab gases, electrical conduits, and corrosion-resistant plumbing. While we are in the walls, let’s replace the wooden studs with more durable metal studs that resist fire and termite damage. To complete this “kitchen remodeling,” we’ll replace the vinyl flooring with an $10,000 epoxy floor, and the Formica counters with epoxy resin.

We’re going to need to remove the ceilings in order to increase the number of floor joist necessary to handle the increased weight of office, lab and classroom furnishings and equipment. While the ceiling is open, we’ll install the circulating hot water system, designed to serve the lab and restroom, and we’ll upsize the mechanical ductwork to meet the new airflow requirements. Speaking of airflow, that “whooshing” sound will be distracting in the classroom so we will need to put in sound attenuation devices.

To meet institutional standards, the wooden windows will need to be replaced with metal, commercial grade windows that have energy-efficient glazing. Similarly, the roof shingles will need to be replaced with slate, due to concerns about life cycle maintenance and architectural consistency. While we’re on the roof, let’s screen the unsightly mechanical systems. Oh yeah, we can’t forget to do something about the pigeons.

Let’s look at the outside again, just for a minute. Only the front façade was bricked when your house was originally constructed, so we’ll need to install bricks on the other three sides. After all, your house is now on campus and our university is trying to project a certain sense of place.

At this point, we have more scope than budget. Money is running out, and there are more things we need to do to bring your house into compliance with our institutional standards. What happened here? In trying to comply with the more stringent codes, reduce future operating costs, address aesthetic requirements, and meet programmatic needs we exceeded the funds available for this renovation. For the money this renovation will cost, you really could build a nice house. But, not on our campus!

About the Authors:

Don Guckert is Vice President of APPA Advisors, a member service providing customized assessments of educational facilities organizations. He previously served as the Associate Vice President for Facilities Management for the University of Iowa and as Director of Planning, Design & Construction for the University of Missouri. Don is an APPA Fellow, professional engineer, former APPA President, and current dean and faculty member for APPA’s Institute for Facilities Management.

Jeri King is a retired Assistant Director of Facilities Management for the University of Iowa. Jeri is an APPA Fellow, former APPA Vice President for Information & Research, recipient of APPA’s Meritorious Service Award, editor of Effective and Innovative Practices for the Strategic Facilities Manager and coauthor of two award winning Facilities Manager articles.